SPECIAL COLLECTION:

Carnivorous Plants

Carnivorous plants have adaptations to lure and trap animals, and absorb nutrients from their bodies.

Most carnivorous plants are relatively small, and incapable of preying on anything larger than insects (the term "insectivorous plant" is sometimes used), though a few are known to trap lizards, rodents, and small birds.

Carnivorous plants have chlorophyll and can use photosynthesis to make carbohydrates, like ordinary plants.

But, they grow in habitats with poor soil, and benefit from the extra nitrogen and other nutrients that they can obtain from capturing animals.

The Venus' flytrap (Dionaea) is probably the most famous carnivorous plant, with modified leaves that snap shut to trap and digest insect prey.

Visitors to the UConn greenhouses can also see Aldrovanda, an aquatic plant that is the closest living relative of the Venus' flytrap.

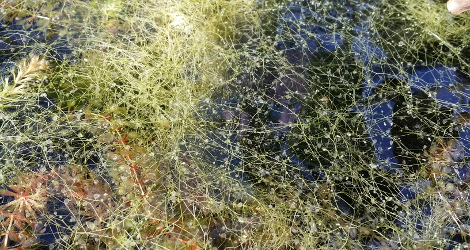

Bladderworts (Utricularia) possess tiny but intricate traps that use suction to snare microscopic prey.

The Venus' flytrap (Dionaea) is probably the most famous carnivorous plant, with modified leaves that snap shut to trap and digest insect prey.

Visitors to the UConn greenhouses can also see Aldrovanda, an aquatic plant that is the closest living relative of the Venus' flytrap.

Bladderworts (Utricularia) possess tiny but intricate traps that use suction to snare microscopic prey.

Other carnivorous plants have leaves that cannot move rapidly like the flytrap's, but instead rely on sticky secretions to immobilize prey.

The sundews (Drosera) have leaves with glandular hairs, each of which produces a drop of mucilaginous glue.

Other plants in the UConn collections with flypaper-type traps include the Portugese sundew (Drosophyllum), the butterworts (Pinguicula), and Roridula, a shrub from South Africa with leaves covered in a resinous adhesive that is powerful enough to hold small birds.

Other carnivorous plants have leaves that cannot move rapidly like the flytrap's, but instead rely on sticky secretions to immobilize prey.

The sundews (Drosera) have leaves with glandular hairs, each of which produces a drop of mucilaginous glue.

Other plants in the UConn collections with flypaper-type traps include the Portugese sundew (Drosophyllum), the butterworts (Pinguicula), and Roridula, a shrub from South Africa with leaves covered in a resinous adhesive that is powerful enough to hold small birds.

The pitcher plants are carnivorous plants with leaves modified as "pitfall" traps. Pitcher plants have urn-like leaves with slick sides, and a pool of liquid inside. Insects (and sometimes larger prey) are attracted to the pitchers by nectar, sweet scents, or colorful patterns.

If the insects lose their footing and slide into the liquid, they drown and are digested and absorbed by the plant.

Pitcher-type traps have evolved independently in three different, unrelated families of flowering plant: the Sarraceniaceae (American pitcher plants), the Nepenthaceae (tropical pitcher plants) and the Cephalotaceae (Albany pitcher plant).

The pitcher plants are carnivorous plants with leaves modified as "pitfall" traps. Pitcher plants have urn-like leaves with slick sides, and a pool of liquid inside. Insects (and sometimes larger prey) are attracted to the pitchers by nectar, sweet scents, or colorful patterns.

If the insects lose their footing and slide into the liquid, they drown and are digested and absorbed by the plant.

Pitcher-type traps have evolved independently in three different, unrelated families of flowering plant: the Sarraceniaceae (American pitcher plants), the Nepenthaceae (tropical pitcher plants) and the Cephalotaceae (Albany pitcher plant).

In cultivation, carnivorous plants require specialized conditions. The soil should be acidic and low in nutrients: here at the UConn greenhouses, we grow most species in a mix of five parts sphagnum peat moss, two parts perlite, and one part horticultural charcoal.

Almost all carnivores do best in humid conditions, and soil that is constantly wet. The plants should be watered with rain or deionized water, to avoid mineral accumulation in the soil.

Most species also require high light levels, and the bulk of the UConn collection is kept in the very sunniest part of the greenhouse complex.

In cultivation, carnivorous plants require specialized conditions. The soil should be acidic and low in nutrients: here at the UConn greenhouses, we grow most species in a mix of five parts sphagnum peat moss, two parts perlite, and one part horticultural charcoal.

Almost all carnivores do best in humid conditions, and soil that is constantly wet. The plants should be watered with rain or deionized water, to avoid mineral accumulation in the soil.

Most species also require high light levels, and the bulk of the UConn collection is kept in the very sunniest part of the greenhouse complex.

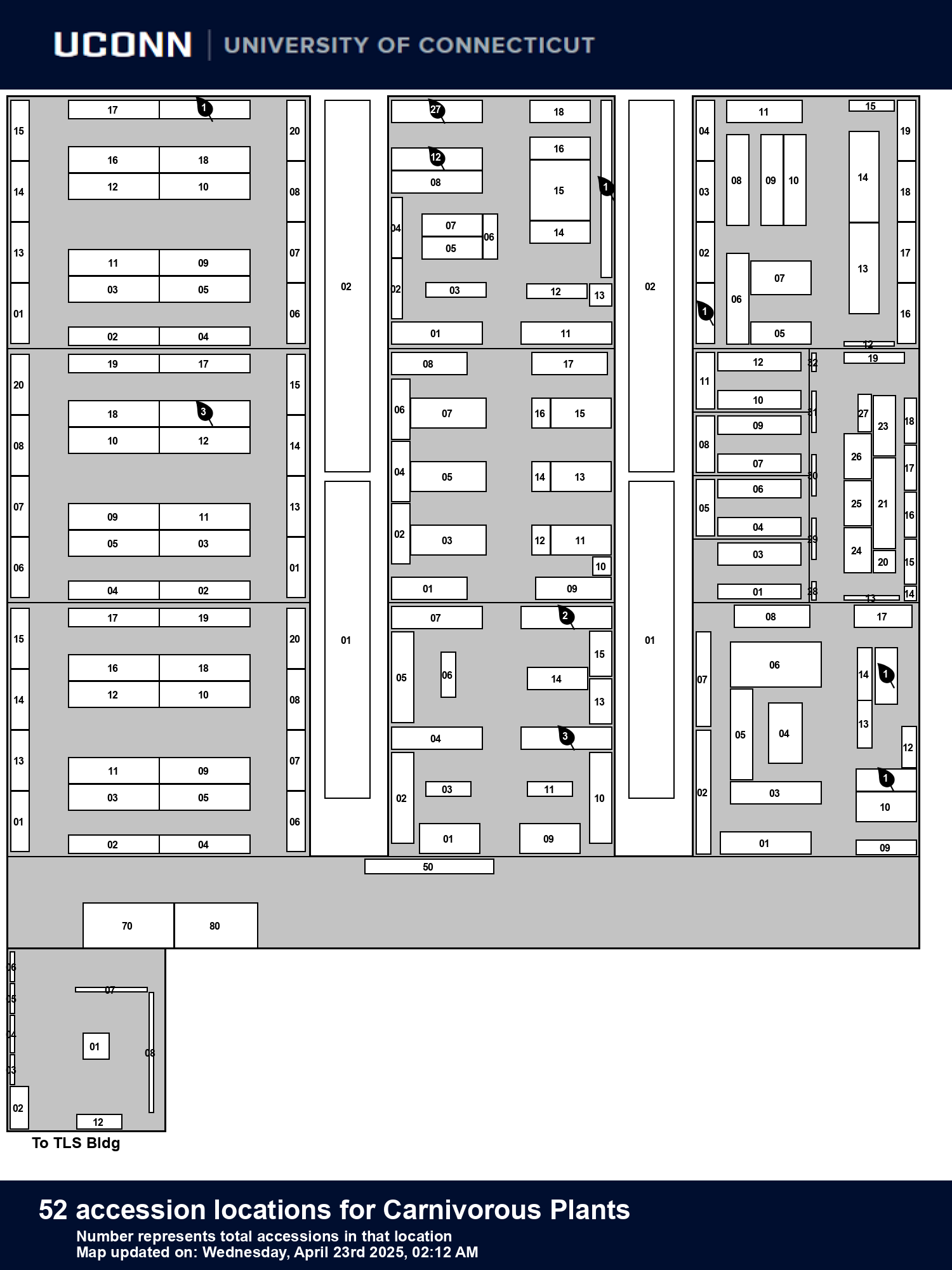

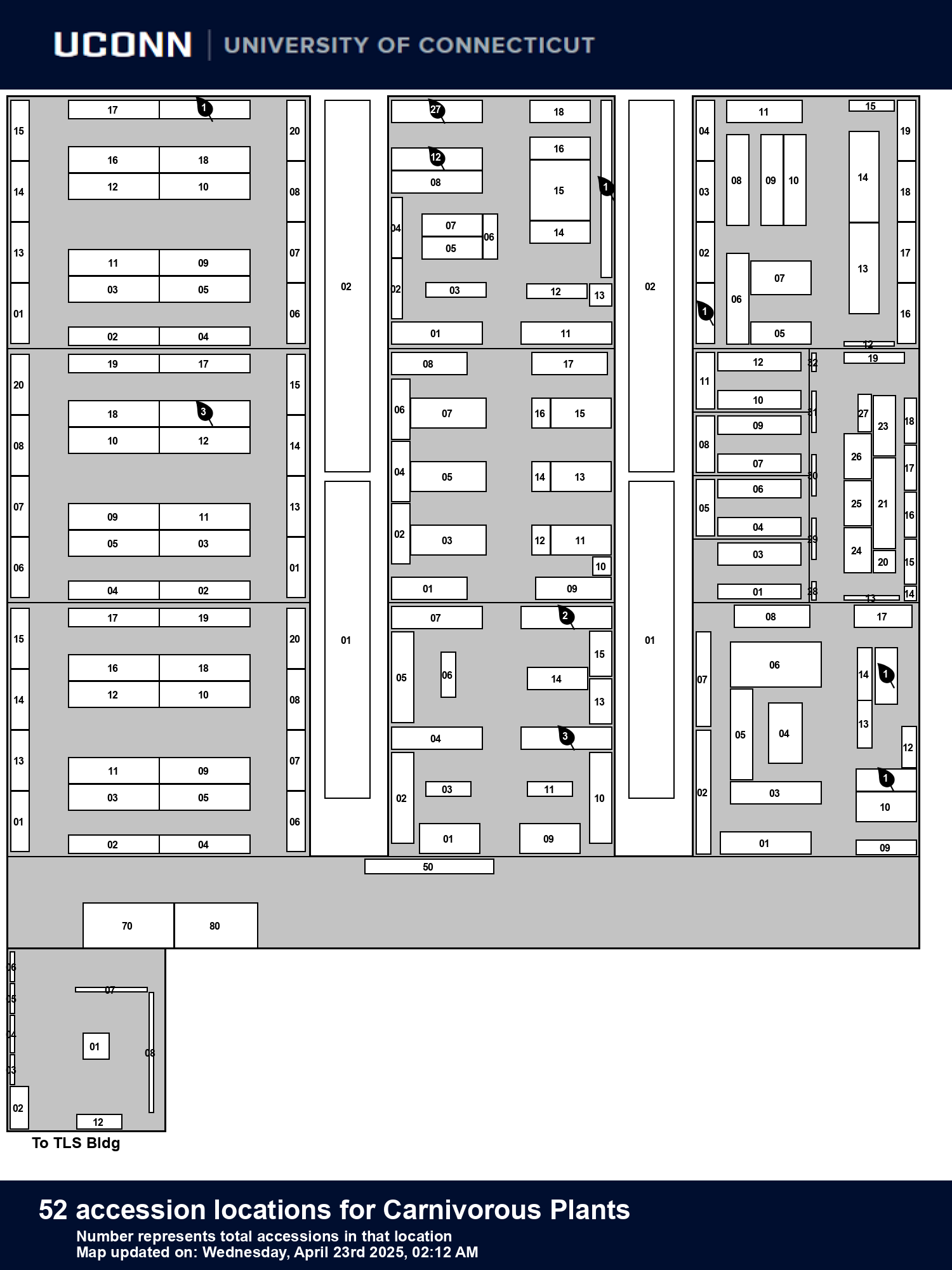

Greenhouse Locator Map:

A more detailed discussion of the morphology & evolution of carnivorous plants can be found on the ICPS Website

Greenhouse Locator Map:

data regenerated on Wed, 09 Jul 2025 02:12:22 -0400

55 Accessions:

Number in parentheses references locator map icons

- {1} Nepenthes alata - Winged Nepenthes - Nepenthaceae

- {1} Nepenthes maxima - The Great Pitcher Plant - Nepenthaceae

- {1} Nepenthes mirabilis - Tropical Pitcher Plant - Nepenthaceae

W/C

W/C - {2} Brocchinia reducta - Brocchinia - Bromeliaceae

- {3} Drosera regia - King Sundew - Droseraceae

W/C

W/C - {3} Roridula dentata - Bug Plant - Roridulaceae

- {3} Roridula gorgonias - Fly Bush - Roridulaceae

- {4} Pinguicula agnata - cv. 'True Blue' - Lentibulariaceae

- {4} Pinguicula moranensis - Butterwort - Lentibulariaceae

- {5} Byblis liniflora - Rainbow Plant - Byblidaceae

- {5} Cephalotus follicularis - Albany Pitcher Plant - Cephalotaceae

- {5} Cephalotus follicularis - Albany Pitcher Plant - Cephalotaceae

- {5} Drosera capensis - Cape Sundew - Droseraceae

W/C

W/C - {5} Drosera capillaris - Pink or Spathulate-leaved Sundew - Droseraceae

W/C

W/C - {5} Drosera cuneifolia - Droseraceae

- {5} Drosera dielsiana - Droseraceae

- {5} Genlisea hispidula - Corkscrew Plant - Lentibulariaceae

- {5} Pinguicula lusitanica - Pale Butterwort - Lentibulariaceae

- {5} Sarracenia alata - Pale Pitcher Plant - Sarraceniaceae

W/C

W/C - {5} Utricularia dichotoma - Fairy Aprons - Lentibulariaceae

- {5} Utricularia livida - Bladderwort - Lentibulariaceae

- {6} Aldrovanda vesiculosa - Waterwheel Plant - Droseraceae

W/C

W/C - {6} Dionaea muscipula - Venus Fly Trap - Droseraceae

- {6} Drosera aliciae - Alice Sundew - Droseraceae

W/C

W/C - {6} Drosera auriculata - Small Eared Sundew - Droseraceae

- {6} Drosera binata - Fork-leaved Sundew - Droseraceae

W/C

W/C - {6} Drosera binata - Fork-leaved Sundew - Droseraceae

- {6} Drosera binata var. multifida extrema - Droseraceae

- {6} Drosera callistos - Droseraceae

- {6} Drosera filiformis var. filiformis - Thread-leaf Sundew - Droseraceae

W/C

W/C - {6} Drosera filiformis var. tracyi - Tracy's Thread Leafed Sundew - Droseraceae

- {6} Drosera pygmaea - Droseraceae

W/C

W/C - {6} Drosera ramellosa - Droseraceae

- {6} Drosera spatulata ssp. lovellae - Droseraceae

W/C

W/C - {6} Drosophyllum lusitanicum - Portuguese Sundew - Drosophyllaceae

- {6} Sarracenia alata - Pale Pitcher Plant - Sarraceniaceae

W/C

W/C - {6} Sarracenia alata - Pale Pitcher Plant - Sarraceniaceae

W/C

W/C - {6} Sarracenia flava - Yellow Pitcher Plant - Sarraceniaceae

- {6} Sarracenia flava var. flava - Yellow Pitcher Plant, Huntsman's Horn - Sarraceniaceae

W/C

W/C - {6} Sarracenia flava var. rubricorpa - Sarraceniaceae

- {6} Sarracenia leucophylla - White Top Pitcher Plant - Sarraceniaceae

- {6} Sarracenia minor - Hooded Pitcher Plant - Sarraceniaceae

- {6} Sarracenia oreophila - Green Pitcher Plant - Sarraceniaceae

W/C

W/C - {6} Sarracenia psittacina - Parrot Pitcher Plant - Sarraceniaceae

- {6} Sarracenia purpurea - Purple Pitcher Plant - Sarraceniaceae

- {6} Sarracenia rosea - Burk's Southern Pitcher Plant - Sarraceniaceae

- {6} Sarracenia rubra ssp. alabamensis - cane-break pitcher plant - Sarraceniaceae

- {6} Sarracenia rubra ssp. jonesii - Mountain Sweet Pitcher Plant - Sarraceniaceae

W/C

W/C - {7} Utricularia gibba - Humped Bladderwort - Lentibulariaceae

- {8} Nepenthes truncata - Tropical Pitcher Plant - Nepenthaceae

- {9} Nepenthes copelandii - Nepenthaceae

W/C

W/C - {10} Catopsis sp. - Bromeliaceae

- {0} Sarracenia purpurea ssp. purpurea - Purple Pitcher Plant - Sarraceniaceae W/C

- {0} Drosera hartmeyerorum - Droseraceae

- {0} Utricularia vulgaris subsp. macrorhiza - Common Bladderwort - Lentibulariaceae

W/C

W/C - WISHLIST ITEM: Ibicella lutea - Martyniaceae

W/C = Wild Collected

= Currently Flowering

= Currently Flowering = Image(s) Available

= Image(s) Available = map available for this accession

= map available for this accession

= voucher(s) on file at CONN for this accession

= voucher(s) on file at CONN for this accession = accession added within past 90 days

= accession added within past 90 days